This poem describes the period commonly referred to as the Enlightenment.

There are vivid scholarly discussions surrounding locality (was there a “European Enlightenment” or is it nearer to truth to discern the French, German, Scottish Enlightenment?), chronology (did the radical proceed to the moderate: did Spinoza “shock” us into the Enlightenment?) and its critiques (is the label merely an ex-post definition by later countermovements?).

However, one thing is sure, it was a period in time that Philosophy was political and “in the world”. When the French Revolution ended the Ancien Régime, the philosophical enlightenment was claimed as its prime reason.

Fin de l’ancien régime

Without the need for (and truth of)

clerical claims and theological games,

a void was filled, in the Land of Letters1

by writers: the new pacesetters.

It is them I honour, in no particular order,

because chronology is outdated and historicity overrated,

who really knows, and by what sufficient reason,

what caused the cause of the Enlightenment season?

In this simple poem of respectful esteem,

I tell the story of the fin de l’ancien régime.

Some say it is clear, what was provoked,

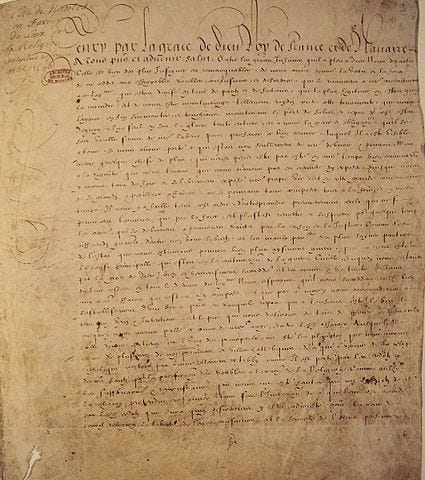

when the Edict of Nantes was revoked:

Calvinist Huguenots fled from France

and found the Dutch to be morally advanced2.

Because seen by all was the division of religion,

papist monarchs versus a reading republic,

the need for knowledge, current and clear,

did set all that changed in the next gear.

Fideist believers were scientific frontrunners,

scientists did still read fate in stars,

scepticism worked out in both ways

because if nothing is known, then not even that?3

There is no way to conclusively know

who read what and what was read,

but we cannot deny the centre of glare,

the man of the moment by the name of Voltaire!

Making fun of the notion of misfortune’s reason

by posing the world as the best there could be,

(as Leibniz described in his reaction to Bayle,

who declared rational theology as a categorical fail),

Voltaire places Candide’s story on thought leaders’ bookshelf,

in this fun little story… oh you’d better read it yourself ;)4

Voltaire then, he raised the pedestal,

for the all powerful Newton the Incredible,

who showed and laid the foundations,

of true knowledge based on observations5.

But threatened by materialistic nightmares,

Bishop Berkeley joined the public affairs,

and claimed no such thing could exist,

“to be is to be perceived!” joked this idealist6.

Afraid of Hobbes, who teaches a material soul,

Berkeley tries some rearguard damage control,

so in a rebuttal to ideas from John Locke,

he cancels the physical world - does he mock?

Meanwhile, corroding deism,

in an undercurrent of radical Spinozism,

De la Mettrie has the first mover junked7

and the Trois Imposteurs are being debunked,

a wind of atheism brings a fresh breeze

and reforming morals for fabulous bees.

I hint to Mandeville, his humming hive,

because in economics I arrive:

Does division of labour decrease the morals

or does wealth bring empathy is the quarrel.

Read Smith and Ferguson, but more than this,

read the news because it is,

a contemporary challenge, still in this time,

centuries later, when I end this rhyme8.

Because there’s so much more to tell and teach,

the further in the books I reach,

more to learn about the Early Enlightenment,

when if not god: philosophy was benevolent.

Literacy rates grew rapidly, and French was now the chosen language for correspondence. The intellectual community shared their ideas in handwritten letters and is commonly referred to as the Republic of Letters.

The revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 ended the religious tolerance of the French. Important and highly educated French philosophers and noble man fled to Holland, where they were welcomed in the universities and cities. This led to the dogma of religious tolerance as a prime part of any definition of The Enlightenment.

At first sight, this is the double-ended sword of scepticism and the rise of the scientific method. If science (more accurate in this period of time is the word philosophy) cannot reach truth, if human reason has its limits, then only faith resting on faith is the path to truth.

This comes very close to Plato’s critique of scepticism. Ultimately, the sceptic tells us: No proposition is true. Plato cleverly asks, “including this proposition?”.

Candide, travelling in a world full of sorrow, is constantly reminded that this world is “the best of all possible worlds”. This refers to Leibniz’ Theodicy (1709), written as a reaction to Bayle not being able to comprehend the presence of evil in the world.

Voltaire translated Newtons Pricipia Mathematica. Disregarding contemplative essences or definitions, Newton is a pure empiricist, working from observations to general principles: forces of nature. This extensive work was difficult to understand, and it is said we have to thank Voltaire for the distributing of Newtons’ Natural Sciences among the European thinking community.

Berkeley argued that the perception of objects is their ontological cause. In this immaterial view, there is no way to poses knowledge of any existence of external objects without direct perceiver (Esse est percipi). Enter God, the omnipresent perceiver.

Julien Offray de La Mettrie is best known for his L’Homme Machine, Man a Machine (1748). For him, matter is not inert and his metaphysic does not need an explanatory immortal soul for life (contra Descartes). As frogs seem to emerge out of a pool without a prime mover, nature is self moving. He is an example of the mental space for atheism in this time period (He was clearly a Spinozist, leaving aside the discussion if pantheism would be a better categorisation of his philosophy).

Adam Smith is known as the Godfather of modern Economics due to his book The Wealth of Nations (1776). He advocates a growth of communities by the division of labour and the increase in private property. In trading of goods (including non-commercial goods such as gifts, originating out of sympathy (See his Theory on Moral Sentiments (1759)) society can flourish. Self-interest and other-interest coincide.

Adam Ferguson, a friend of his (until a quarrel later in life) partly criticises this commercial society, making men less concerning about their society. As a driver of growth, collective knowledge and innovation, for him, are more important than wealth.

Now, in the 21st century, we can ask in hindsight; do we regard the accumulators of wealth as the moral guides for our society, or the accumulators of knowledge?